Ludwig Wittgenstein

| Ludwig Wittgenstein | |

|---|---|

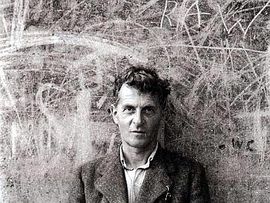

Photographed by Ben Richards in Swansea, 1947 |

|

| Born | April 26, 1889 Vienna, Austria |

| Died | April 29, 1951 (aged 62) Cambridge, England |

| Cause of death | Prostate cancer |

| Resting place | Ascension Parish Burial Ground, Cambridge |

| Education | PhD (Cantab) |

| Alma mater | Victoria University of Manchester, University of Cambridge |

| Occupation | Philosopher, schoolteacher |

| Known for | Private language argument, language-game, family resemblance, picture theory of language, rule-following paradox |

| Notable works | Tractatus Logico-Philosophicus (1921), Philosophical Investigations (1953) |

| Parents | Karl Wittgenstein and Leopoldine Kalmus |

| Relatives | Paul Wittgenstein, brother; Margaret Stonborough-Wittgenstein, sister; Friedrich von Hayek, mother's nephew |

| Website | |

| The Cambridge Wittgenstein archive | |

Ludwig Josef Johann Wittgenstein (26 April 1889 – 29 April 1951) was an Austrian philosopher who worked primarily in the areas of logic, philosophy of mathematics, philosophy of mind, and philosophy of language. He held the position of professor of philosophy at the University of Cambridge from 1939 until 1947, preceded by G.E. Moore and followed by G.H. von Wright.[1]

Described by Bertrand Russell as a perfect example of genius: "passionate, profound, intense, and dominating," Wittgenstein inspired two of the century's principal philosophical movements, logical positivism and ordinary language philosophy. Professional philosophers have ranked his Philosophical Investigations (1953) and Tractatus Logico-Philosophicus (1921) numbers one and four respectively in a list of the most important philosophy books of the 20th-century.[2] Peter Hacker writes that 20th-century philosophy would be as unintelligible without Wittgenstein as 20th-century art without Picasso.[3]

Born into one of Europe's wealthiest families in Vienna at the turn of the century—a city and time Bruce Duffy described as a dark hothouse of soil that produced not only Wittgenstein, but also Sigmund Freud, Karl Kraus, Theodor Herzl, and Adolf Hitler—he gave away his inheritance, and was at one point reduced to selling his furniture to cover expenses when working on the Tractatus.[4] He was gay long before it was accepted, as was at least one of his brothers, three of whom committed suicide, with Wittgenstein and the remaining brother both contemplating it.[5] He approached philosophy at Cambridge as pointless and almost offensive; he grew angry with students who wanted to pursue it, and himself tried to leave, working as a primary school teacher in Austria, where he found himself in trouble for hitting the children, and during the Second World War as a medical orderly in Guy's Hospital. He famously embraced G.E. Moore's wife when she told him she was working in a jam factory—doing something useful, in Wittgenstein's eyes.[6]

His work is usually divided between his early period, exemplified by the Tractatus, the only philosophy book he published in his lifetime, and his later period, articulated in the Investigations. The early Wittgenstein was concerned with the relationship between propositions and the world, and saw the aim of philosophy as nothing more than correcting misconceptions about language through logical abstraction. The Tractatus became a leading text of logical atomism, the Vienna Circle, and later logical positivism: logical truths were tautologies and metaphysical claims nonsensical—not wrong, but simply meaningless.[3] The later Wittgenstein rejected many of the conclusions of the Tractatus, and provided a detailed account of the many possible uses of ordinary language, calling language a series of interchangeable language-games in which the meaning of words is derived from their public use; thus there can be no such thing as a private language. Despite these differences, similarities between the early and later periods include a conception of philosophy as a kind of therapy, a concern for ethical and religious themes, and a literary style often described as poetic. Terry Eagleton called him the philosopher of poets and composers, playwrights and novelists.[7]

Background

The Wittgensteins

Wittgenstein's paternal great-grandfather was Moses Meier, a Jewish land agent in Laasphe, in the Principality of Wittgenstein in Westphalia (see Schloss Wittgenstein).[9]The son of Meyer Moses, he decided to adopt the name Wittgenstein for himself in 1808, becoming Moses Meier-Wittgenstein. With his wife, Brendel Simon, he built up a large trading business. His son, Hermann Christian Wittgenstein, married Fanny Figdor Kittseee, who converted to Protestantism when they married. They had 11 children, among them Karl Wittgenstein, Wittgenstein's father.[10]

Karl made a fortune in iron and steel, and by the late 1880s was one of the richest men in the world.[8] He transferred much of his capital into real estate, shares of stocks, precious metals, and foreign currency reserves, spread across Switzerland, Austria, the Netherlands and North America, which insulated the family's colossal wealth from the inflation crises that followed.[11]

Early life

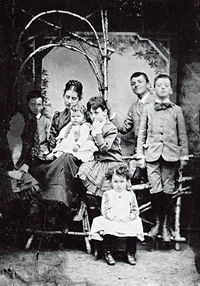

Wittgenstein was born in Vienna to Karl and his wife, Leopoldine Kalmus, known as Poldi, Jewish on her father's side and Roman Catholic on her mother's.[11] Karl and Poldi had nine children in all: four girls—Hermine, the first born, Margaret, known as "Gretl," and Helene, with a fourth daughter dying as a baby; and five boys—Hans, Kurt, Rudolf (Rudi), Paul, who became a well-known concert pianist despite losing an arm in the war, and Ludwig, the youngest.[12]

The children were baptized as Catholics, and raised in a household that provided an exceptionally intense environment for artistic and intellectual achievement. Karl was a leading patron of the arts, commissioning works by Auguste Rodin and financing the Vienna Secession Building. Gustav Klimt painted Wittgenstein's sister for her wedding portrait; Johannes Brahms, Gustav Mahler, Bruno Walter, Clara Schumann, and Pablo Casals gave concerts in the family's home. Brahms even gave two of the sisters piano lessons,[13] though Alexander Waugh writes that the oldest sister, Hermine, was so nervous of Brahms that when she was once allowed to sit with him at dinner, she spent most of the evening vomiting in one of the bathrooms.[14]

Karl's aim was to turn his sons into captains of industry; instead, three of them committed suicide, Paul became a concert pianist, and Wittgenstein a philosopher after a brief period as an engineer.[10] The Irish psychiatrist Michael Fitzgerald argues that Karl was a harsh perfectionist who lacked empathy, and that Wittgenstein's mother was anxious and insecure, unable to stand up to her husband.[15] Whatever the reason, the family had a strong streak of depression running through it, or what Anthony Gottlieb called bad temper and extreme nervous tension. He tells a story about Paul practicing one day on one of the family's seven grand pianos. He leapt up and shouted at Wittgenstein in the next room: "I cannot play when you are in the house, as I feel your skepticism seeping towards me from under the door!"[16] Fitzgerald and the Swedish psychiatrist Christopher Gillberg argue that Wittgenstein showed several features of high-functioning autism; German psychiatrist Sula Wolff suggests he suffered from schizoid personality disorder.[15]

The eldest of his brothers, Hans, may also have suffered from autism. Alexander Waugh writes that Hans's first word was "Oedipus"; at the age of four, he could identify the Doppler effect in a passing siren as a quarter-tone drop in pitch, and at five started crying "Wrong! Wrong!" when two brass bands in a carnival played the same tune in different keys. He was hailed as a musical genius, and was probably gay; he died in mysterious circumstances in May 1902, possibly a suicide. Exactly year later, aged 22 and studying chemistry at the Berlin Academy, his brother Rudi walked into a bar, asked the pianist to play Thomas Koschat's "Verlassen, verlassen, verlassen bin ich," then mixed himself a drink of milk and potassium cyanide, dying in agony. Gottlieb writes that his suicide note said he was grieving over the death of a friend, but it was more likely that he was worried about what he called his "perverted disposition." He had looked for help from the Scientific Humanitarian Committee, which campaigned against Section 175 of the German Criminal Code forbidding unnatural sexual acts. The organization published an annual report, including a case study that Rudi feared identified him as the subject. His father forbade the family from mentioning his name ever again.[5]

Kurt shot himself at the end of the First World War, when the Austrian troops he was commanding deserted en masse in October 1918. Gottlieb writes that Hermine had said Kurt seemed to carry "the germ of disgust for life within himself." Wittgenstein himself considered suicide, as did Paul.[16] Wittgenstein told a friend, David Pinsent, that when Bertrand Russell first encouraged him in his philosophy in January 1912, it had ended nine years of his loneliness and feelings of suicide.[17]

Education

1903: Realschule in Linz

Wittgenstein was educated at home until 1903, when he began three years of schooling at the Staatsoberrealschule in Linz, lodging nearby with a family called Strigl.[18] Historian Brigitte Hamann writes that he stood out from the other boys and was bullied; he spoke an unusually pure form of High German with a stutter, dressed elegantly, and was sensitive and unsociable. His first impression of the school, recorded in a notebook, was "Crap!" (Mist!). [13]

Adolf Hitler was a student at the same school, but was two grades below Wittgenstein, though they were born just six days apart.[19] Ray Monk, one of Wittgenstein's biographers, writes that the boys were both there during the school year 1904–1905, but there is disagreement as to whether they would have known each another.[20] Hamann argued in Hitler's Vienna (1996) that Hitler was bound to have laid eyes on Wittgenstein, because the latter was so conspicuous,[13] though she told Focus magazine they were in different classes and would have had nothing to do with one another.[21]

Hitler referred in Mein Kampf to a Jewish boy at the school: "At the Realschule I knew one Jewish boy. We were all on our guard in our relations with him, but only because his reticence and certain actions of his warned us to be discreet. Beyond that my companions and myself formed no particular opinion in regard to him.[23] Hamann writes that there were 17 Jews in the school at the time.[13]

Several commentators have written that a photograph of Hitler taken at the school (see right; Hitler is the boy on the top right) shows Wittgenstein in the lower left corner,[22] but Hamann told Focus the photograph stems from 1900 or 1901, before Wittgenstein's time.[24] Laurence Goldstein argues in Clear and Queer Thinking (1999) that it was "overwhelmingly probable" the boys met each other. He writes that Hitler, vicious and aggressive, would have viewed with "envy, hatred and mistrust that stammering, precocious, precious, aristocratic upstart who ... disdainfully flaunted his wealth and superiority."[25] Commentators have reacted angrily to the suggestion that Wittgenstein's wealth and unusual personality may have fed Hitler's antisemitism; reviewing his book, Marie McGinn calls Goldstein's position sloppy and irresponsible.[26]

According to Alexander Waugh, Wittgenstein and Hitler were both misfits, insisting the other children address them with the formal German "Sie."[18] Wittgenstein was often absent and did not do well; Harmann writes that when he went to university in Berlin in 1906, his spelling was little better than Hitler's.[13] He received an A only twice, both times in religious studies. The rest of his grades were usually C or D, sometimes a B and once an E. The other boys made fun of him, singing after him: "Wittgenstein wandelt wehmütig widriger Winde wegen Wienwärts" ("Wittgenstein wends his woeful windy way towards Vienna").[20]

1906: Engineering in Berlin and Manchester

In 1906 he began studying mechanical engineering in Berlin, and after graduating in 1908 he went to the Victoria University of Manchester to do his doctorate, full of plans for aeronautical projects. At Manchester he conducted research into the behavior of kites in the upper atmosphere, experimenting at a meteorological observation states near Glossop. He also worked on the design of a propeller with small jet engines on the end of its blades, something he patented in 1911 and which earned him a research studentship from the university.[27] It was around this time that he became interested in the foundations of mathematics, particularly after reading Alfred North Whitehead and Bertrand Russell's Principia Mathematica (1910), and Gottlob Frege's Grundgesetze der Arithmetik, vol. 1 (1893) and vol. 2 (1903).[28] In the summer of 1911 he visited Frege in Jena. He wrote:

I was shown into Frege's study. Frege was a small, neat man with a pointed beard who bounced around the room as he talked. He absolutely wiped the floor with me, and I felt very depressed; but at the end he said "You must come again," so I cheered up. I had several discussions with him after that. Frege would never talk about anything but logic and mathematics, if I started on some other subject, he would say something polite and then plunge back into logic and mathematics.[29]

1911: Arrival at Cambridge

Wittgenstein wanted to study with Frege, but Frege suggested he attend the University of Cambridge to study under Russell, so in October 1911 Wittgenstein arrived unannounced at Russell's rooms in Trinity College.[30] He was soon not only attending Russell's lectures, but dominating them, then following Russell back to his rooms at four or five in the evening to discuss more philosophy until Hall. Russell was irritated by him; he wrote to his lover Lady Ottoline Morrell: "My German friend threatens to be an infliction."[31]

He revised his opinion, and in fact came to be overpowered by Wittgenstein's forceful personality. He wrote in November 1911 that he had at first thought Wittgenstein might be a crank, but soon decided he was a genius: "Some of his early views made the decision difficult. He maintained, for example, at one time that all existential propositions are meaningless. This was in a lecture room, and I invited him to consider the proposition: 'There is no hippopotamus in this room at present.' When he refused to believe this, I looked under all the desks without finding one; but he remained unconvinced."[31]

Three months after Wittgenstein's arrival he told Morrell: "I love him & feel he will solve the problems I am too old to solve ... He is the young man one hopes for."[32] The role-reversal between him and Wittgenstein was such that he wrote in 1916, after Wittgenstein had criticized his own work: "His criticism, 'tho I don't think he realized it at the time, was an event of first-rate importance in my life, and affected everything I have done since. I saw that he was right, and I saw that I could not hope ever again to do fundamental work in philosophy."[33]

1912: Moral Sciences Club and Apostles

In 1912 Wittgenstein joined the Cambridge Moral Sciences Club, an influential discussion group for philosophy dons and students.[34] Wittgenstein delivered his first paper there on 29 November that year, a four-minute talk defining philosophy as "all those primitive propositions which are assumed as true without proof by the various sciences."[35] From that point on he dominated the society, to the point where special starred meetings had to be organized, meaning dons were not supposed to attend, though everyone knew the arrangement was intended only to deter Wittgenstein. He had to stop attending entirely in the 1930s after complaints that no one else had the chance to speak during meetings.[34]

The club became known outside philosophy after a meeting on 25 October 1946 at Richard Braithwaite's rooms in King's, with Sir Karl Popper, another Viennese philosopher, as the guest speaker. Popper's paper was "Are there philosophical problems?", in which he struck up a position in contradiction to Wittgenstein's, contending that problems in philosophy are substantive, and not just linguistic puzzles as Wittgenstein argued. Accounts vary as to what happened next, but it seems Wittgenstein became infuriated and started waving a hot poker at Popper, demanding that Popper give him an example of moral rule. Popper offered one—"Not to threaten visiting speakers with pokers"— at which point Russell had to tell Wittgenstein to put the poker down, and Wittgenstein stormed out. It was the only time the three philosophers, three of the most eminent in the world, were ever in the same room together.[36] The minutes record that the meeting was "charged to an unusual degree with a spirit of controversy."[37]

John Maynard Keynes also invited him to Wittgenstein to join the Cambridge Apostles, an elite secret society formed in 1820, which both Russell and Moore had joined as students, but Wittgenstein did not enjoy it and attended infrequently. Russell had been worried that Wittgenstein, with his literal-mindedness, would not appreciate the group's humour and self-affectation. Lytton Strachey wrote to Keynes on 17 May 1912 about an Apostles meeting Wittgenstein had attended, calling him Herr Sinckel-Winckel:

Oliver and Herr Sinckel-Winckel hard at it on universals and particulars. The latter oh! so bright—but quelle souffrance! Oh God! God! "If A loves B"—"There may be a common quality"—"Not analysable that way at all, but the complexes have certain qualities." How shall I manage to slink off to bed?[38]

1912–1913: Relationship with David Pinsent

It was Russell who introduced Wittgenstein to David Hume Pinsent (1891–1918) in the summer of 1912. A mathematics undergraduate and descendant of David Hume, Pinsent became what Wittgenstein called his first and only friend,[39] and is widely regarded as the first of three or four men Wittgenstein fell in love with—followed by Francis Skinner in 1930, Ben Richards in the late 1940s, and to a lesser extent Keith Kirk in 1940—though Pinsent and Kirk did not respond in kind.[40]

The men worked together on experiments in the psychology laboratory about the role of rhythm in the appreciation of music, and Wittgenstein delivered a paper about it to the British Psychological Association in Cambridge in 1912. They also travelled together, including to Iceland in September 1912—the expenses paid by Wittgenstein's father, including first-class travel, and new clothes and spending money for Pinsent—and later to Norway. Pinsent's diaries have provided researchers with a wealth of material about Wittgenstein's personality, and what comes across strongly is how sensitive and nervous he was, attuned to the tiniest slight or change in mood from Pinsent, with Pinsent reguarly writing that Wittgenstein was in a huff about something.[41] He wrote about shopping for furniture with Wittgenstein in Cambridge when the latter was given rooms in Trinity; most of what they found in the stores was not frugal enough for Wittgenstein's taste:[38]

I went and helped him interview a lot of furniture at various shops ... It was rather amusing: he is terribly fastidious and we led the shopman a frightful dance, Vittgenstein [sic] ejaculating "No—Beastly!" to 90 percent of what he shewed us!"[38]

He wrote in May 1912 that Wittgenstein had just begun to study philosophy: "[h]e expresses the most naive surprise that all the philosophers he once worshipped in ignorance are after all stupid and dishonest and make disgusting mistakes!"[38] The last time they saw each other was at Birmingham train station on 8 October 1913, when they said goodbye before Wittgenstein left to live in Norway. Despite the physical distance that had grown between them because of the war—Pinsent's last letter to Wittgenstein was dated 14 September 1916—when Pinsent died in a plane crash in May 1918, Wittgenstein was distraught to the point of suicidal, and three years later dedicated the Tractatus to him.[38]

1914–1918: World War I

Military service

Karl Wittgenstein died on 20 January 1913, and on receiving his inheritance Wittgenstein became one of the wealthiest men in Europe.[42] He donated some of it, initially anonymously, to Austrian artists and writers, including Rainer Maria Rilke and Georg Trakl. In 1914, he went to visit Trakl, when the latter wanted to meet his benefactor, but Trakl died in an apparent suicide days before Wittgenstein arrived. This is the second instance, after Ludwig Boltzmann in 1906, of someone committing suicide just when Wittgenstein wanted to meet them.

Wittgenstein came to feel that he could not get to the heart of his most fundamental questions while surrounded by other academics, and so in 1913 he retreated to the village of Skjolden in Norway, where he rented the second floor of a house for the winter. The isolation allowed him to devote himself to his work, and he later saw this period as one of the most productive of his life, writing Logik, the predecessor of much of the Tractatus.[30]

The outbreak of World War I the next year left him in deep shock. He volunteered for the Austro-Hungarian army, first serving on a ship and then in an artillery workshop. In March 1916, he was posted to a fighting unit on the front line of the Russian front, as part of the Austrian 7th Army, where his unit was involved in some of the heaviest fighting, defending against the Brusilov Offensive.[43] In action against British troops, he was decorated with the Military Merit with Swords on the Ribbon, and was commended by the army for "courageous behaviour, calmness, sang-froid, and heroism."[44] In January 1917, he was sent as a member of a howitzer regiment to the Russian front, where he won several medals for bravery including the Silver Medal for Valour.[43] In 1918 he was promoted to reserve officer (lieutenant) and sent to northern Italy as part of an artillery regiment. For his part in the Austrian offensive of June 1918, he was recommended for the Gold Medal for Valour, the highest honour in the Austrian army, but was instead awarded the Band of the Military Service Medal with Swords.[45]

Throughout the war, he kept notebooks in which he frequently wrote philosophical reflections alongside personal remarks, and in them he records his contempt for the baseness of soldiers in wartime. He discovered Leo Tolstoy's The Gospel in Brief at a bookshop in Galicia, and carried it everywhere, recommending it to anyone in distress to the point where he became known to his fellow soldiers as "the man with the gospels".[46]

Publication of the Tractatus

On leave in the summer of 1918, he received a letter from David Pinsent's mother telling him that Pinsent had been killed in an airplane accident on 8 May.[47] Suicidal, Wittgenstein went to stay with his uncle Paul, and there completed the Tractatus, which he dedicated to Pinsent. The book was sent to publishers, but without success. In October 1918, he returned to the Italian front but was captured by the Italians shortly thereafter.[30] Through the intervention of Russell and Keynes, he managed to get access to books, prepare his manuscript, and send it back to England. Russell saw it as a work of supreme philosophical importance and worked with Wittgenstein to get it published after his release in 1919. He wrote an introduction, lending the book his reputation, though Wittgenstein had become personally disaffected with Russell and thought the introduction evinced a fundamental misunderstanding of the Tractatus.[48]

It first appeared in German in 1921 as "Logisch-Philosophische Abhandlung," published as part of Wilhelm Ostwald's journal Annalen der Naturphilosophie, though Wittgenstein was not happy with the end result and called it a pirate edition. An English translation was prepared by Frank Ramsey, a mathematics undergraduate at King's commissioned by C. K. Ogden. After some discussion of how best to translate the German title, Moore suggested Tractatus Logico-Philosophicus, an allusion to Baruch Spinoza's Tractatus Theologico-Politicus. Difficulties remained in finding a publisher, in part because Wittgenstein wanted it to appear without Russell's introduction; Cambridge University Press turned it down for that reason. Finally in 1922 Routledge & Kegan Paul agreed to print a bilingual edition with Russell's introduction and the Ramsey-Ogden translation.[49]

1920: Teaching in Austria

| "At the basis of the whole modern view of the world lies the illusion that the so-called laws of nature are the explanations of natural phenomena.

"So people stop short at natural laws as at something unassailable, as did the ancients at God and Fate." |

| — Wittgenstein, Tractatus, 6.371–6.372 |

By 1920, Wittgenstein was a profoundly changed man. He had faced harrowing combat in World War I, and crystallized his intellectual and emotional upheavals with the exhausting composition of the Tractatus. Because he believed it offered a definitive solution to all the problems of philosophy, he decided to leave for Austria to work as a primary school teacher, where he worked in several schools in Hassbach, Otterthal, and Trattenbach.[50] He was unhappy, writing to Russell in October 1921:

I am still at Trattenbach, surrounded, as ever, by odiousness and baseness. I know that human beings on the average are not worth much anywhere, but here they are much more good-for-nothing and irresponsible than elsewhere.[51]

Frank Ramsey, the translator of the Tractatus, went to visit him in the fall of 1923 and wrote in a letter home that Wittgenstein was living very economically, in one tiny whitewashed room that only had space for a bed, washstand, a small table, and one small hard chair. Ramsey shared an evening meal with him of coarse bread, butter, and cocoa. His school hours were eight to twelve or one, and he had afternoons free.[52]

While there Wittgenstein wrote a 42-page pronunciation and spelling dictionary for the children, Wörterbuch für Volksschulen, the only book of his apart from the Tractatus that was published in his lifetime. It was published in Vienna in 1926, minus an introduction he wrote for it, by Hölder-Pichler-Tempsky;[49] a first edition sold for £75,000 in 2005.[53] He ran into trouble with the school because he struck the children, and this, together with a general suspicion among the villagers that he was mad, led to a long series of bitter disagreements with some of the children's parents. It culminated in April 1926 when he hit an 11-year-old boy so hard on the head that the child collapsed. The boy's father tried to have Wittgenstein arrested; he was cleared of misconduct, but resigned his position and returned to Vienna, where he worked as a gardener's assistant in the monastery of the Brothers of Mercy in Hütteldorf.[50]

1926: Stonborough House

| "I am not interested in erecting a building, but in ... presenting to myself the foundations of all possible buildings." |

| —Wittgenstein[54] |

In 1926, Wittgenstein was invited by his sister Gretl to work on the design of her new house. The architect was Paul Engelmann, who had become his friend during the war, when they spent a lot of time in each other's company in the trenches. Engelmann designed a spare modernist house after the style of Adolf Loos. Wittgenstein poured himself into the project, focusing on the windows, doors, and radiators. It took him a year to design the door handles, and another to design the radiators. Each window was covered by a metal screen that weighed 150kg, moved by a pulley Wittgenstein designed. Bernhard Leitner, author of The Architecture of Ludwig Wittgenstein, said of it that there is barely anything comparable in the history of interior design: "It is as ingenious as it is expensive. A metal curtain that could be lowered into the floor." When the house was nearly finished he had a ceiling raised 30mm so that he had the exact proportions he wanted.[50]

Ludwig's eldest sister, Hermine, wrote of the house that even though she admired it: "I always knew that I neither wanted to, nor could, live in it myself. It seemed indeed to be much more a dwelling for the gods." Wittgenstein himself found the house too austere, saying it had good manners, but no primordial life and no health.[54] After the war it became a barracks and stables for Russian soldiers, and in the 1950s Gretl's son sold it to a developer. The Vienna Landmark Commission saved it and made it a national monument in 1971, and it now houses the cultural department of the Bulgarian Embassy.[50]

Vienna Circle

Toward the end of his work on the house, Wittgenstein was contacted by Moritz Schlick, one of the leading figures of the newly formed Vienna Circle. The Tractatus had been tremendously influential in the development of Viennese positivism and, although Schlick never succeeded in drawing Wittgenstein into the discussions of the Vienna Circle itself, he and some of his fellow circle members, especially Friedrich Waismann, met occasionally with Wittgenstein to discuss philosophical topics.[55] Wittgenstein was frequently frustrated by these meetings—he believed that Schlick and his colleagues had fundamentally misunderstood the Tractatus. Many of the disagreements concerned the importance of religious life and the mystical; Wittgenstein considered these matters as a sort of wordless faith, whereas the positivists disdained them as useless. In one meeting, Wittgenstein went so far as to refuse to discuss the book at all, and sat with his back to his guests sulking, while he read aloud from the poetry of Rabindranath Tagore, much to the vexation of his guests. Nevertheless, the contact with the Vienna Circle stimulated Wittgenstein intellectually and revived his interest in philosophy. In the course of his conversations with the Vienna Circle and Frank Ramsey, who travelled from Cambridge to Austria to discuss the Tractatus, Wittgenstein began to think that there might be some mistakes in his work.

1929–1947: Return to Cambridge

PhD and fellowship

At the urging of Ramsey and others, Wittgenstein returned to Cambridge in 1929. He was met at the railway station by a crowd of England's greatest intellectuals, discovering rather to his horror that he was one of the most famed philosophers in the world. Keynes wrote in a letter to his wife: "Well, God has arrived. I met him on the 5.15 train." Despite this fame, he could not initially work at Cambridge as he did not have a degree, so he applied as an advanced undergraduate. Russell noted that his previous residency was sufficient for a PhD, and urged him to offer the Tractatus as his thesis. It was examined in 1929 by Russell and Moore; at the end of the thesis defence, Wittgenstein clapped the two examiners on the shoulder and said, "Don't worry, I know you'll never understand it."[56] Moore wrote in the examiner's report: "I myself consider that this is a work of genius; but, even if I am completely mistaken and it is nothing of the sort, it is well above the standard required for the Ph.D. degree."[57] Wittgenstein was appointed as a lecturer and was made a fellow of Trinity College.

1938: Anschluss

From 1936 to 1937, Wittgenstein lived again in Norway,[58] where he worked on the Philosophical Investigations. In the winter of 1936/37, he delivered a series of "confessions" to close friends, most of them about minor infractions like white lies, in an effort to cleanse himself. In 1938, he traveled to Ireland to visit Maurice Drury, a friend who was training as a doctor, and considered such training himself, with the intention of abandoning philosophy for psychiatry. The visit to Ireland was at the same time a response to the invitation of the then Irish Taoiseach, Eamon de Valera, himself a mathematics teacher. De Valera hoped that Wittgenstein's presence would contribute to an academy for advanced mathematics.

While he was in Ireland in March 1938, Germany annexed Austria in the Anschluss; the Viennese Wittgenstein was now a citizen of the enlarged Germany and a Jew under its racial laws. He and his siblings had been raised as Christians, but they were Jews under the Nuremberg racial laws, because three of their grandparents had been born as Jews and had converted to Christianity only as adults. Wittgenstein found this intolerable and started to investigate the possibility of acquiring British or Irish citizenship with the help of Keynes. A few days before the invasion of Poland, Hitler granted Mischling (Jewish-Aryan half-breed) status to the Wittgenstein children. In 1939 there were 2,100 applications for this, and Hitler granted only 12.[59] Anthony Gottlieb writes that the pretext was that their paternal grandfather had been the bastard son of a German prince, which allowed the Reichsbank to claim the gold, foreign currency, and stocks held in Switzerland by a Wittgenstein trust. Gretl, an American citizen by marriage, was the one who started the negotiations over the racial status of their grandfather, and the family's foreign currency was used as a bargaining tool. Paul had escaped to Switzerland and then the United States in July 1938, and disagreed with the negotiations, leading to a permanent split between the siblings. After the war, when Paul was performing in Vienna, he did not visit Hermine who was dying there, and he had no further contact with Ludwig or Gretl.[16]

1939: Professorship

After G. E. Moore's resigned the chair in philosophy in 1939, Wittgenstein was appointed, and acquired British citizenship soon afterwards. In July 1939 he travelled to Vienna to assist Gretl and his other sisters, visiting Berlin for one day to meet an official of the Reichsbank. After this, he travelled to New York to persuade Paul, whose agreement was required, to back the scheme. The required Befreiung was granted in August 1939. The unknown amount signed over to the Nazis by the Wittgenstein family, a week or so before the outbreak of war, included amongst many other assets 1.7 tonnes of gold.[60] At 2009 prices, this amount of gold alone would be worth in excess of US$60 million. There is also a report that Wittgenstein went on to visit Moscow a second time in 1939, travelling from Berlin, and again met the philosopher Sophia Janowskaya.[61]

After work, Wittgenstein would often relax by watching Westerns, where he preferred to sit at the very front of the cinema, or reading detective stories.[62] Norman Malcolm wrote that he would rush to the cinema when class ended. "As the members of the class began to move their chairs out of the room he might look imploringly at a friend and say in a low tone, ‘Could you go to a flick?’ On the way to the cinema Wittgenstein would buy a bun or cold pork pie and munch it while he watched the film."[63]

By this time, Wittgenstein's view on the foundations of mathematics had changed considerably. Earlier he had thought that logic could provide a solid foundation, and he had even considered updating Russell and Whitehead's Principia Mathematica. Now he denied that there were any mathematical facts to be discovered and he denied that mathematical statements were true in any real sense. He gave a series of lectures on mathematics, discussing this and other topics, documented in a book, with lectures by Wittgenstein and discussions between him and several students, including the young Alan Turing.[64]

World War II

During World War II, he left Cambridge and volunteered as a hospital porter in Guy's Hospital in London and as a laboratory assistant in Newcastle's Royal Victoria Infirmary. This was arranged by his friend John Ryle, a brother of the philosopher Gilbert Ryle, who was then working at the hospital. After the war, Wittgenstein returned to teach at Cambridge, but he found teaching an increasing burden: he had never liked the intellectual atmosphere at Cambridge, and in fact encouraged several of his students, including Skinner, to find work outside of academic philosophy. There are stories, perhaps apocryphal, that if any of his philosophy students expressed an interest in pursuing the subject, he would ban them from attending any more of his classes.

Personal relationships and politics

Although Wittgenstein was involved in a relationship with Marguerite Respinger (a young Swiss woman he had met as a friend of the family), his plans to marry her were broken off in 1931 and he never married. Most of his romantic attachments were to young men. There is considerable debate over how active Wittgenstein's homosexual life was, inspired by the American philosopher William Warren Bartley's biography, Wittgenstein (1973), in which material was presented alleging that Wittgenstein had several casual liaisons with young men in the Wiener Prater park during his time in Vienna. Bartley said he had discovered two coded notebooks unknown to Wittgenstein's executors that detailed the visits to the Prater.[65] Wittgenstein's estate and other biographers disputed Bartley's claims and asked him to produce his sources. What became clear is that Wittgenstein had several long-term attachments with men, including relationships with David Pinsent, Francis Skinner, and Ben Richards.[66]

Although some commentators have assumed that Wittgenstein's political sympathies lay on the left, and while he once described himself as a "communist at heart" and romanticized the life of laborers,[67] in many ways he was a reactionary. He abhorred the idea of scientific progress, because it was meaningless without moral progress, was conservative in his musical tastes, and was ambivalent about the invention of nuclear weapons, stating that "the people making speeches against producing the bomb are undoubtedly the scum of the intellectuals, although even this does not prove beyond question that what they abominate is to be welcomed".[68] He particularly admired the philosophy of the Austrian Otto Weininger. Wittgenstein distributed copies of Weininger's theories to bemused colleagues at Cambridge.[69] Like Weininger, Wittgenstein had a troubled relationship towards his ethnicity and sexuality.[70] In his notebooks of the early 1930s, in particular MS 154, he berated himself for being a "reproductive" as opposed to "productive" thinker, and attributed this to his own Jewish and diasporadic sense of identity, writing: "The saint is the only Jewish genius. Even the greatest Jewish thinker is no more than talented. (Myself for instance)".[71] While Wittgenstein would later say that his thoughts are "100% Hebraic,"[72] as Hans Sluga has argued, "his was a self-doubting Judaism, which had always the possibility of collapsing into a destructive self-hatred (as it did in Weininger's case) but which also held an immense promise of innovation and genius."[73]

In 1934, attracted by Maynard Keynes's description of Soviet life in Short View of Russia, he conceived the idea of emigrating to the Soviet Union with Francis Skinner. They took lessons in Russian and in 1935 Wittgenstein traveled to Leningrad and Moscow to look for a job. He was offered teaching positions but preferred manual work and returned three weeks later.

1947–1951: Final years and death

| "Death is not an event in life: we do not live to experience death. If we take eternity to mean not infinite temporal duration but timelessness, then eternal life belongs to those who live in the present. Our life has no end in the way in which our visual field has no limits." |

| — Wittgenstein, Tractatus, 6.431 |

He resigned his position at Cambridge in 1947 to concentrate on his writing. He was succeeded as professor by his friend Georg Henrik von Wright. He stayed at Kilpatrick House guesthouse in East Wicklow in 1947 and 1948. Much of his later work was done on the west coast of Ireland in the rural isolation he preferred with Patrick Lynch. By 1949, when he was diagnosed as having prostate cancer, he had written most of the material that would be published after his death as Philosophische Untersuchungen (Philosophical Investigations).

He spent the last two years of his life in Vienna, the United States, Oxford, and Cambridge, where he worked continuously on new material, inspired by the conversations that he had had with his friend and former student Norman Malcolm during a summer spent at the Malcolms' house in the United States. Malcolm had been wrestling with G.E. Moore's common sense response to external world skepticism ("Here is one hand, and here is another; therefore I know at least two external things exist"). Wittgenstein spent the last eighteen months of his life writing his Remarks on Colour, inspired by Goethe's Theory of Colours. In it, he "examines the features of different colours (metallic colour, the colours of flames, etc.) and of luminosity, a theme Wittgenstein treats in such a way as to destroy the traditional idea that colour is a simple and logically uniform kind of thing.[74]

In the days before his death, He began to work on another series of remarks inspired by his conversations, published posthumously as On Certainty. He wrote the final entry, in manuscript MS 177, less than a day before he completely lost consciousness.[75] His last words, reported by the wife of his doctor in whose home he spent his last days, were: "Tell them I've had a wonderful life".[76] He was buried at the Ascension Parish Burial Ground in Cambridge.

Work

The Tractatus (1921)

Apart from the 1926 dictionary for schoolchildren in Austria, the Tratactus was the only book Wittgenstein published in his lifetime. Russell wrote an introduction for it to explain to publishers why it was important; the book may not have been published otherwise given how difficult it was for both the lay reader and specialist to understand. Nevertheless Wittgenstein was not happy with it. He had lost faith in Russell, finding him glib and his philosophy too mechanistic. He also felt Russell had fundamentally misunderstood the Tractatus.[77]

The work was first published with Russell's introduction in Germany in 1921, as Logisch-philosophische Abhandlung, part of Wilhelm Ostwald's Annalen der Naturphilosophie, but Wittgenstein saw the editing as slovenly and called it a "Raubdruck" (pirate publication). He submitted it to Cambridge University Press without the Russell introduction, but they rejected it for that reason. Several other publishers also turned it down, but Routledge and Kegan Paul accepted it for publication in 1922—again, with the introduction—translated by Frank P. Ramsey, who was commissioned by C. K. Ogden.[49]

This is the translation that was approved by Wittgenstein, but it is problematic in a number of ways. Wittgenstein's English was poor at the time, and Ramsey was a teenager, a mathematics undergraduate, who had only recently learned German. For example, "Sachverhalt" and "Sachlage" are translated as "atomic fact" and "state of affairs" respectively. But Wittgenstein discusses non-existent "Sachverhalten," and there cannot be a non-existent fact. In a later translation (1961), David Pears and Brian McGuinness made a number of changes, including translating "Sachverhalt" as "state of affairs" and "Sachlage" as "situation." The new translation is often preferred, but some philosophers use the original, in part because Wittgenstein approved it, and because it avoids the idiomatic English of Pears-McGuinness.[78]

The book is 75 pages long, and presents seven numbered propositions (1–7), with sub-levels elaborating on the basic propositions (1, 1.1, 1.11):

- Die Welt is alles, was der Fall ist.

- Ramsey-Ogden: The world is everything that is the case.

- Pears-McGuinness: The world is all that is the case.

- Was der Fall ist, die Tatsache, ist das Bestehen von Sachverhalten.

- Ramsey-Ogden: What is the case, the fact, is the existence of atomic facts.

- Pears-McGuinness: What is the case—a fact—is the existence of states of affairs.

- Das logische Bild der Tatsachen ist der Gedanke.

- Ramsey-Ogden: The logical picture of the facts is the thought.

- Pears-McGuinness: A logical picture of facts is a thought.

- Der Gedanke ist der sinnvolle Satz.

- Ramsey-Ogden: The thought is the significant proposition.

- Pears-McGuinness: A thought is a proposition with a sense.

- Der Satz ist eine Wahrheitsfunktion der Elementarsätze.

- Ramsey-Ogden: Propositions are truth-functions of elementary propositions.

- Pears-McGuinness: A proposition is a truth-function of elementary propositions.

- Die allgemeine Form der Wahrheitsfunktion ist:

![[\bar p,\bar\xi, N(\bar\xi)]](/I/01a3cf5f91211db95ef402b4bd20508b.png) . Dies ist die allgemeine Form des Satzes.

. Dies ist die allgemeine Form des Satzes.

- Ramsey-Ogden: The general form of truth-function is:

![[\bar p,\bar\xi, N(\bar\xi)]](/I/01a3cf5f91211db95ef402b4bd20508b.png) . This is the general form of proposition.

. This is the general form of proposition. - Pears-McGuinness: The general form of a truth-function is:

![[\bar p,\bar\xi, N(\bar\xi)]](/I/01a3cf5f91211db95ef402b4bd20508b.png) . This is the general form of a proposition.

. This is the general form of a proposition.

- Ramsey-Ogden: The general form of truth-function is:

- Wovon man nicht sprechen kann, darüber muß man schweigen.

- Ramsey-Ogden: Whereof one cannot speak, thereof one must be silent.

- Pears-McGuinness: What we cannot speak about we must pass over in silence.

| "The main point is the theory of what can be expressed (gesagt) by prop[osition]s—i.e. by language—(and, which comes to the same, what can be thought) and what can not be expressed by pro[position]s, but only shown (gezeigt); which I believe, is the cardinal problem of philosophy." |

| — Wittgenstein, letter to Russell, 19 August 1919.[79] |

The Tractatus presents the idea of logical atomism and the picture theory of meaning. Wittgenstein argues that the world consists of facts, not objects—the world is the totality of facts, not of things (1.1)—and that our experience of it can be reduced to a set of atomic facts that can be analyzed no further. The obtaining of a state of affairs is a fact. A representation of a state of affairs is a model or picture; the totality of true thoughts is a picture of the world (3.01).[80]

Thus, propositions are logical pictures, which may be true or false, just as a state of affairs obtains or does not obtain. Language makes claims about the world only when there is something in common between propositions and what they picture. A statement that cannot be reduced to atomic facts is meaningless, or nonsense.[80]

The truths of metaphysics, ethics, religion, and aesthetics are ineffable; they can be shown but not said. For Wittgenstein, the job of the philosopher is simply to monitor the bounds of sense.[80] He wrote in the preface: "The book will, therefore, draw a limit to thinking, or rather—not to thinking, but to the expression of thoughts; for, in order to draw a limit to thinking we should have to be able to think both sides of this limit (we should therefore have to be able to think what cannot be thought)." Because the limit can only be drawn in language, what lies beyond it is nonsense.[81] The Tractatus itself is constructed of pseudo-propositions, as Wittgenstein acknowledges:

6.54 My propositions are elucidatory in this way: he who understands me finally recognizes them as senseless, when he has climbed out through them, on them, over them. (He must so to speak throw away the ladder, after he has climbed up on it.[82]

Intermediate works

Wittgenstein wrote copiously after his return to Cambridge, and arranged much of his writing into an array of incomplete manuscripts. Some thirty thousand pages existed at the time of his death. Much, but by no means all, of this has been sorted and released in several volumes.[83] During his "middle work" in the 1920s and 1930s, much of his work involved attacks from various angles on the sort of philosophical perfectionism embodied in the Tractatus. Of this work, Wittgenstein published only a single paper, "Remarks on Logical Form," which was submitted to be read to the Aristotelian Society and published in their proceedings. By the time of the conference, however, Wittgenstein had repudiated the essay as worthless, and gave a talk on the concept of infinity instead, but he was too late to prevent the publication and requested that the synopsis be omitted from the synoptic index of the journal that came out in 1954.[84]

Wittgenstein was increasingly frustrated to find that, although he was not yet ready to publish his work, some other philosophers were beginning to publish essays containing inaccurate representations of his own views, based on their conversations with him. As a result, he published a very brief letter to the journal Mind, taking a recent article by Richard Braithwaite as a case in point, and asked philosophers to hold off writing about his views until he was himself ready to publish them.

Philosophical Investigations

Although unpublished during his lifetime, the Blue Book, a set of notes dictated to his class at Cambridge in 1933–1934, contains seeds of Wittgenstein's later thoughts on language—later developed in the Philosophical Investigations (Philosophische Untersuchungen)—and is widely read today as a turning-point in his philosophy of language.

The Philosophical Investigations (PI) was published in two parts in 1953, two years after Wittgenstein's death. Most of the 693 numbered paragraphs in Part I were ready for printing in 1946, but Wittgenstein withdrew the manuscript from the publisher. The shorter Part II was added by the editors, G.E.M. Anscombe and Rush Rhees.

It is difficult to find consensus among interpreters of Wittgenstein's work, and this is particularly true in the case of the Investigations. Wittgenstein asks the reader to think of language and its uses as a multiplicity[85] of language-games within which the parts of language function and have meaning. From this perspective, many conventional philosophical problems (e.g. what is truth?) become meaningless wordplay.

The conventional view of the task of the philosopher is to solve seemingly intractable problems of philosophy using logical analysis (for example, the problem of free will, the relationship between mind and matter, what the good or the beautiful or the true consist of, the nature of meaning, and so on). However, Wittgenstein argues that these problems are, in fact, "bewitchments" that arise from philosophers' misguided attempts to consider the words' absolute meanings, outside of context, usage, and grammar, as if there were some ultimate abstract foundation for the meaning of a word all by itself. Rather than indulge in this fantasy, one should understand the meanings of words, even abstract, philosophical words, by looking at how the words are used by fluent speakers. The beginning of The Blue Book puts flesh on the late Wittgenstinian project by applying it to the word "meaning" itself:

What is the meaning of a word? Let us attack this question by asking, first,...what does the explanation of a word look like? The way this question helps us is analogous to the way the question 'how do we measure a length?' helps us to understand the problem 'what is length?'

In Wittgenstein's view, language is inextricably woven into the fabric of life, and as part of that fabric it works relatively unproblematically. We do not, when speaking ordinarily, worry about how our words mean what they do. Philosophical problems arise when language is forced from its proper home and into a metaphysical environment, where all the familiar and necessary landmarks and contextual clues are removed, specifically for the purpose of "pure" philosophical examination. Wittgenstein describes this metaphysical environment as like being on frictionless ice:[86] where the conditions are apparently perfect for a philosophically and logically perfect language (the language of the Tractatus), where all philosophical problems can be solved without the confusing and muddying effects of everyday contexts; but where, just because of the lack of friction, language can in fact do no actual work at all. There is much talk in the Investigations, then, of "idle wheels" and language being "on holiday" or a mere "ornament", all of which is used to express the idea of what is lacking in philosophical contexts. To resolve the problems encountered there, Wittgenstein argues that philosophers must leave the frictionless ice and return to the "rough ground" of ordinary language in use; that is, philosophers must "bring words back from their metaphysical to their everyday use."

In this regard, one can see affinities between Wittgenstein and Kant.[87] In the Critique of Pure Reason, Kant argues that when concepts grounded in experience are applied outside of the range of possible experience, the result is contradictions and confusion. Thus, the second part of the Critique consists of refutations, typically by reductio ad absurdum, of logical proofs of the existence of God and the existence of souls, and attacks on strong notions of infinity and necessity. In this way, Wittgenstein's objections to applying words outside the contexts in which they have an established meaning mirror Kant's objections to the non-empirical use of empirical reason.

Returning to the rough ground of ordinary uses of words is, however, easier said than done. Philosophical problems have the character of depth and run as deep as the forms of language and thought that set philosophers on the road to confusion. Wittgenstein therefore speaks of "illusions", "bewitchment", and "conjuring tricks" performed on our thinking by our forms of language, and tries to break their spell by attending to differences between superficially similar aspects of language which he feels lead to this type of confusion. For much of the Investigations, then, Wittgenstein tries to show how philosophers are led away from the ordinary world of language in use by misleading aspects of language itself. He does this by looking at the role language plays in the development of various philosophical problems, to some general problems involving language itself, then at the notions of rules and rule following, and then on to some more specific problems in the philosophy of mind. Throughout these investigations, the style of writing is conversational, with Wittgenstein in turn taking the role of the puzzled philosopher (on either or both sides of traditional philosophical debates), and that of the guide attempting to show the puzzled philosopher the "way out of the fly bottle."[88]

Much of the Investigations, then, consists of examples of how philosophical confusion is generated and how, by a close examination of the actual workings of everyday language, the first false steps towards philosophical puzzlement can be avoided. By avoiding these first false steps, philosophical problems themselves simply no longer arise and are therefore dissolved rather than solved. As Wittgenstein puts it, "the clarity we are aiming at is indeed complete clarity. But this simply means that the philosophical problems should completely disappear."

Reception

Both his early and later work have been major influences in the development of analytic philosophy. Former colleagues and students include Gilbert Ryle, Friedrich Waismann, Norman Malcolm, G. E. M. Anscombe, Rush Rhees, Georg Henrik von Wright, Peter Geach and the Buddhist scholar K.N. Jayatilleke. Contemporary philosophers influenced by him are too numerous to mention, but they include Cora Diamond, James F. Conant and Stanley Cavell who are associated with the New Wittgenstein. Saul Kripke has published his own interpretation of Philosophical Investigations in Wittgenstein on Rules and Private Language, which came to be dubbed by critics "Kripkenstein".

Some have criticized Wittgenstein for his position on the limits of language, and his abandonment of rigorous stepwise analysis in favor of empirical linguistic description in his later works. His friend Friedrich Waismann, who spent much of the 1930s unsuccessfully attempting to co-author a book with Wittgenstein, accused him of "complete obscurantism" because of his apparent betrayal of logical positivism and empirical inquiry,[89] a criticism that was developed by Ernest Gellner.[90]

He was influential outside philosophy too. Patrick Lynch's thinking as an economist was affected by Wittgenstein's visits to Ireland and the holidays they spent in the west of the country. Psychologists and psychotherapists inspired by Wittgenstein's work include Fred Newman, Lois Holzman, Brian J. Mistler, and John Morss. American anthropologist Clifford Geertz grounded his development of linguistic symbolism in Wittgenstein's work, while the French sociologist, Pierre Bourdieu, said that "Wittgenstein is probably the philosopher who has helped me most at moments of difficulty. He's a kind of saviour for times of great intellectual distress".[91] The writings and art work of conceptual artist, Joseph Kosuth, is heavily influenced by Wittgensteinian thought. American composer Steve Reich has twice set quotes from Wittgenstein to music. "How small a thought it takes to fill a whole life!" is the basis for Proverb (1995), while the third movement of You Are (Variations) (2004), uses a sentence from Philosophical Investigations: "Explanations come to an end somewhere."[92] Elizabeth Lutyens set parts of the Tractatus to music in 1951. A movie about Wittgenstein's life was made by Derek Jarman with a script by Terry Eagleton in 1993. The only known fragment of music composed by Wittgenstein was premiered in November 2003; it comprises four bars and lasts less than half a minute.[93]

Works

A collection of Ludwig Wittgenstein's manuscripts is held by Trinity College, Cambridge.

- Logisch-Philosophische Abhandlung, Annalen der Naturphilosophie, 14 (1921)

- Tractatus Logico-Philosophicus, translated by C.K. Ogden (1922)

- Philosophische Untersuchungen (1953)

- Philosophical Investigations, translated by G.E.M. Anscombe (1953)

- Bemerkungen über die Grundlagen der Mathematik, ed. by G.H. von Wright, R. Rhees, and G.E.M. Anscombe (1956), a selection of his work on the philosophy of logic and mathematics between 1937 and 1944.

- Remarks on the Foundations of Mathematics, translated by G.E.M. Anscombe, rev. ed. (1978)

- Bemerkungen über die Philosophie der Psychologie, ed. G.E.M. Anscombe and G.H. von Wright (1980)

- Remarks on the Philosophy of Psychology, Vols. 1 and 2, translated by G.E.M. Anscombe, ed. G.E.M. Anscombe and G.H. von Wright (1980), a selection of which makes up Zettel.

- The Blue and Brown Books (1958), notes dictated in English to Cambridge students in 1933–1935.

- Philosophische Bemerkungen, ed. by Rush Rhees (1964)

- Philosophical Remarks (1975)

- Philosophical Grammar (1978)

- Bemerkungen über die Farben, ed. by G.E.M. Anscombe (1977)

- Remarks on Colour (1991), remarks on Goethe's Theory of Colours.

- On Certainty, collection of aphorisms discussing the relation between knowledge and certainty, extremely influential in the philosophy of action.

- Culture and Value, collection of personal remarks about various cultural issues, such as religion and music, as well as critique of Søren Kierkegaard's philosophy.

- Zettel, collection of Wittgenstein's thoughts in fragmentary/"diary entry" format as with On Certainty and Culture and Value.

- Works online

- Review of P. Coffey's Science of Logic (1913): a polemical book review, written in 1912 for the March 1913 issue of The Cambridge Review when Wittgenstein was an undergraduate studying with Russell. The review is the earliest public record of Wittgenstein's philosophical views.

- Tractatus Logico-Philosophicus (1922/1923), German text and Ogden-Ramsey translation

- Wittgenstein Source: 5 000 pages of the Wittgenstein Nachlass online

- Works by Ludwig Wittgenstein at Project Gutenberg

- Google Edition of Remarks on Colour

- Some Remarks on Logical Form

- Cambridge (1932–3) lecture notes

- The Blue Book

- Lecture on Ethics

- On Certainty

Notes

- ↑ Dennett, Daniel. "Ludwig Wittgenstein: Philosopher", Time magazine, 29 March 1999.

- ↑ Lackey, Douglas. "What Are the Modern Classics? The Baruch Poll of Great Philosophy in the Twentieth Century", Philosophical Forum. 30 (4), December 1999, pp. 329–346. For a summary, see here, accessed 3 September 2010. For the Russell quote, see McGuinness, Brian. Wittgenstein: A Life : Young Ludwig 1889-1921. University of California Press, 1988, p. 118.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 Hacker, P.M.S.. "Wittgensteinians," in Ted Honderich (ed.). The Oxford Companion to Philosophy. Oxford University Press, 1995, pp. 916–917.

- ↑ Duffy, Bruce. "The do-it-yourself life of Ludwig Wittgenstein", The New York Times, 13 November 1988, p. 2.

- For his selling his furniture, see "Ludwig Wittgenstein: Tractatus and Teaching", Cambridge Wittgenstein archive], accessed 4 September 2010.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 Waugh, Alexander. "The Wittgensteins: Viennese whirl", The Daily Telegraph, 30 August 2008; Gottlieb, Anthony. "A Nervous Splendor", The New Yorker, 9 April 2009.

- ↑ Donagan Alan and Malpas, J.E. The Philosophical Papers of Alan Donagan. University of Chicago Press, 1994, p. x.

- ↑ For ethical and religious themes, see Barrett, Cyril. Wittgenstein on Ethics and Religious Belief. Blackwell, 1991, p. 138.

- For Wittgenstein's philosophy as therapy, see Peterman, James F. Philosophy as Therapy. SUNY Press, 1992, p. 13ff.

- For the poetic and literary quality of his work, see Perloff, Marjorie. Wittgenstein's Ladder: Poetic Language and the Strangeness of the Ordinary. University of Chicago Press, 1999; and Gibson, John and Wolfgang Huemer (eds.). The Literary Wittgenstein. Psychology Press, 2004, p 2.

- For Eagleton, see Eagleton, Terry. "My Wittgenstein" in Stephen Regan (ed.). The Eagleton Reader. Wiley-Blackwell, 1997, pp. 337–338.

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 Bramann, Jorn K. and Moran, John. "Karl Wittgenstein, Business Tycoon and Art Patron", Frostburg State University, accessed 2 September 2010.

- ↑ Various sources spell this Meier, Maier, and Meyer.

- ↑ 10.0 10.1 Kenny, Anthony. "Give Him Genius or Give Him Death", The New York Times, 30 December 1990.

- Also see "Ludwig Wittgenstein: Background", Wittgenstein archive, University of Cambridge, accessed 7 September 2010.

- ↑ 11.0 11.1 "Ludwig Wittgenstein: Background", Wittgenstein archive, University of Cambridge, accessed 2 September 2010.

- ↑ Bartley, William Warren. Wittgenstein. Open Court, 1985, p. 16.

- ↑ 13.0 13.1 13.2 13.3 13.4 Hamann, Brigitte and Thornton, Thomas. Hitler's Vienna: A Dictator's Apprenticeship. Oxford University Press, 2000 (first published 1996 in German) pp. 15–16, 79.

- ↑ Waugh, Alexander. The House of Wittgenstein. Doubleday, 2008. p. 9/

- ↑ 15.0 15.1 Fitzgerald, Michael. "Did Ludwig Wittgenstein have Asperger's syndrome?", European Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, volume 9, number 1, pp. 61–65. DOI: 10.1007/s007870050117

- Also see Fitzgerald, Michael. Autism and Creativity: Is There a Link Between Autism in Men and Exceptional Ability?. Routledge, 2004; see the chapter "Ludwig Wittgenstein," p. 57ff.

- ↑ 16.0 16.1 16.2 Gottlieb, Anthony. "A Nervous Splendor", The New Yorker, 9 April 2009.

- ↑ Monk, Ray. Ludwig Wittgenstein: The Duty of Genius. Penguin, 2001 (first published 1990), p. 41.

- ↑ 18.0 18.1 Waugh, Alexander. The House of Wittgenstein: a Family at War. Random House of Canada, 2009, p. 33.

- ↑ Hitler started at the school on 17 September 1900, repeated the first year in 1901, and left in the autumn of 1905; see Kersaw, Ian. Hitler, 1889-1936. W. W. Norton & Company, 2000, p. 16ff.

- ↑ 20.0 20.1 Monk, Ray. Ludwig Wittgenstein: The Duty of Genius. Penguin, 2001 (first published 1990), p. 15.

- ↑ Thiede, Roger. "Phantom Wittgenstein", Focus magazine, 16 March 1998.

- ↑ 22.0 22.1 For examples of commentators saying the image shows Wittgenstein, see Cornish, Kimberley. The Jew of Linz. Arrow, 1999.

- "Monument to the birth of the 20th century", exhibition at the Galerija Nova, 2006, accessed 8 September 2010, and

- Gibbons, Luke. "An extraordinary family saga", Irish Times, 29 November 2008.

- For an opposing view, see Hamann, Brigitte and Thornton, Thomas. Hitler's Vienna: A Dictator's Apprenticeship. Oxford University Press, 2000, pp. 15–16, 79.

- See the full image at the Bundesarchiv, accessed 8 September 2010. The archives give the date of the image as circa 1901.

- Also see McGuinness, Brian. Wittgenstein: A Life : Young Ludwig 1889-1921. University of California Press, 1988, p. 97ff, and Monk, Ray. Ludwig Wittgenstein: The Duty of Genius. Penguin, 2001 (first published 1990), p. 15.

- ↑ Hitler, Adolf. Mein Kampf. Translated by James Murphy, CreateSpace, 2010, p. 38. The German reads: "In der Realschule lernte ich wohl einen jüdischen Knaben kennen, der von uns allen mit Vorsicht behandelt wurde, jedoch nur, weil wir ihm in bezug auf seine Schweigsam-keit, durch verschiedene Erfahrungen gewitzigt, nicht sonder-lich vertrauten; irgendein Gedanke kam mir dabei so wenig wie den anderen." See the original German edition, published by the Zentralverlag der NSDAP, August Pries GmbH, Leipzig, 1925–1926, p. 55.

- ↑ Thiede, Roger. "Phantom Wittgenstein", Focus magazine, 16 March 1998.

- The German Federal Archives says the image was taken around 1901; it identifies the class as 1B and the teacher as Oskar Langer. See the full image and description at the Bundesarchiv, accessed 6 September 2010. The archive gives the date as circa 1901, but wrongly calls it the Realschule in Leonding, near Linz. Hitler attended primary school in Leonding, but from September 1901 went to the Realschule in Linz itself. See Kershaw, Ian. Hitler, 1889-1936. W. W. Norton & Company, 2000, p. 16ff.

- Christoph Haidacher and Richard Schober write that Langer taught at the school from 1884 until 1901; see Haidacher, Christoph and Schober, Richard. Von Stadtstaaten und Imperien, Universitätsverlag Wagner, 2006, p. 140.

- ↑ Goldstein, Lawrence. Clear and Queer Thinking: Wittgenstein's Development and his Relevance to Modern Thought. Duckworth, 1999, p. 167ff. Also see "Clear and Queering Thinking", review in Mind, Oxford University Press, 2001.

- ↑ McGinn, Marie. "Hi Ludwig," Times Literary Supplement, 26 May 2000.

- ↑ Kanterian, Edward. Ludwig Wittgenstein. Reaktion Books, 2007, p. 29.

- ↑ Beaney, Michael (ed.). The Frege Reader. Blackwell, 1997, pp. 194-223, 258-289.h

- ↑ Kanterian, Edward. Ludwig Wittgenstein. Reaktion Books, 2007, p. 36.

- ↑ 30.0 30.1 30.2 O'Connor, J.J. and Robertson, E.F. "Ludwig Josef Johann Wittgenstein", St Andrews University, accessed 2 September 2010.

- ↑ 31.0 31.1 McGuinness, Brian. Wittgenstein: A Life : Young Ludwig 1889-1921. University of California Press, 1988, pp. 88–89.

- ↑ Monk, p. 41.

- ↑ Russell, Bertrand. Autobiography. Routledge, 1998, p. 281.

- ↑ 34.0 34.1 Edmonds, David and Eidinow, John. Wittgenstein's Poker. Faber and Faber, 2001, p. 22–28.

- ↑ Pitt, Jack. "Russell and the Cambridge Moral Sciences Club", "Russell: the Journal of Bertrand Russell Studies: Vol. 1, issue 2, article 3, winter 1982.

- Also see Klagge, James Carl and Nordmann, Alfred (eds.) Ludwig Wittgenstein: Public and Private Occasions. Rowman & Littlefield, 2003, p. 332, citing Michael Nedo and Michele Ranchetti (eds.). Ludwig Wittgenstein: sein Leben in Bildern und Texten. Suhrkamp, 1983, p. 89.

- ↑ Eidinow, John and Edmonds, David. "When Ludwig met Karl...", The Guardian, 31 March 2001.

- "Wittgenstein's Poker by David Edmonds and John Eidinow", The Guardian, 21 November 2001.

- ↑ Minutes of the Wittgenstein's poker meeting, University of Cambridge, shown on Flickr, accessed 7 September, 2010.

- ↑ 38.0 38.1 38.2 38.3 38.4 Kanterian, Edward. Ludwig Wittgenstein. Reaktion Books, 2007, p. 40.

- ↑ Goldstein, Laurence. Clear and queer thinking: Wittgenstein's development and his relevance to modern thought. Rowman & Littlefield, 1999, p. 179.

- ↑ Monk, Ray. Ludwig Wittgenstein: The Duty of Genius. Penguin, 2001 (first published 1990), pp. 583–586.

- ↑ Monk, Ray. Ludwig Wittgenstein: The Duty of Genius. Penguin, 2001 (first published 1990), p. 58ff.

- ↑ Monk, Ray. Ludwig Wittgenstein: The Duty of Genius. Penguin, 2001 (first published 1990), p. 71.

- ↑ 43.0 43.1 Monk, Ray. Ludwig Wittgenstein: The Duty of Genius. Penguin, 2001 (first published 1990), pp.137–142.

- ↑ Waugh, Alexander. The House of Wittgenstein: a Family at War. Random House of Canada, 2009, p. 114.

- ↑ Monk, Ray. Ludwig Wittgenstein: The Duty of Genius. Penguin, 2001 (first published 1990), p. 154.

- ↑ Monk, Ray. Ludwig Wittgenstein: The Duty of Genius. Penguin, 2001 (first published 1990), pp. 44, 116, 382–384. He was not that widely read in philosophy, something he freely acknowledged: his other influences included Saint Augustine, Fyodor Dostoevsky and Søren Kierkegaard. He told the Moral Sciences Club around 1929 that Kierkegaard was a saint; see Creegan, Charles. Wittgenstein and Kierkegaard: Religion, Individuality and Philosophical Method. Routledge, 1989, chapter one.

- ↑ For an original report, see "Death of D.H. Pinsent," Birmingham Daily Mail, May 15, 1918: "Recovery of the Body. The body of Mr. David Hugh Pinsent, a civilian observer, son of Mr and Mrs Hume Pinsent, of Foxcombe Hill, near Oxford and Birmingham, the second victim of last Wednesday's aeroplane accident in West Surrey, was last night found in the Basingstoke Canal, at Frimley." Courtesy of "Wittgenstein in Birmingham", mikeinmono, 3 August 2009, accessed 7 September 2010.

- ↑ See Russell, Bertrand. Introduction, Tractatus Logico-Philosophicus, May 1922.

- ↑ 49.0 49.1 49.2 "Ludwig Wittgenstein: Tractatus and Teaching", Cambridge Wittgenstein archive], accessed 4 September 2010.

- ↑ 50.0 50.1 50.2 50.3 Jeffries, Stuart. "A dwelling for the gods", The Guardian, 5 January 2002.

- ↑ Klagge, James Carl. Wittgenstein: Biography and Philosophy. Cambridge University Press, 2001, p. 185.

- ↑ Mellor, D.H. "Cambridge Philosophers I: F. P. Ramsey", Philosophy 70, 1995, pp. 243–262.

- ↑ Ezard, John. "Philosopher's rare 'other book' goes on sale", The Guardian, 19 February 2005.

- ↑ 54.0 54.1 Hyde, Lewis. "Making It". The New York Times, 6 April 2008.

- ↑ Uebel, Thomas. "Vienna Circle", Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy, 28 June 2006.

- ↑ Monk, Ray. Ludwig Wittgenstein: The Duty of Genius. Penguin, 2001 (first published 1990), p. 271.

- ↑ R. B. Braithwaite George Edward Moore, 1873 - 1958, in Alice Ambrose and Morris Lazerowitz. G.E. Moore: Essays in Retrospect. Allen & Unwin, 1970.

- ↑ Ludwig Wittgenstein: Return to Cambridge from the Cambridge Wittgenstein Archive

- ↑ Edmonds, David and Eidinow, John. Wittgenstein's Poker. Faber and Faber, 2001, pp. 98, 105.

- ↑ Edmonds, David and Eidinow, John. "Wittgenstein’s Poker", Faber and Faber, London 2001, p. 98.

- ↑ Moran, John. "Wittgenstein and Russia" New Left Review 73, May–June, 1972, pp. 83–96.

- ↑ Hoffmann, Josef. "Hard-boiled Wit: Ludwig Wittgenstein and Norbert Davis", CADS, no. 44, October 2003.

- ↑ Malcolm, Norman. Ludwig Wittgenstein: A Memoir. Oxford University Press, 1958, p. 26.

- ↑ Diamond, Cora (ed.). Wittgenstein's Lectures on the Foundations of Mathematics. University Of Chicago Press, 1989.

- ↑ Bartley, William Warren. Wittgenstein. Open Court, 1985, p. 160.

- ↑ Monk, Ray. Ludwig Wittgenstein: The Duty of Genius. Penguin, 2001 (first published 1990), pp. 361, 428 (for Skinner, see pp. 331–334, 376, 401–402; for Richards, see pp. 503–506).

- ↑ Monk, Ray. Ludwig Wittgenstein: The Duty of Genius. Penguin, 2001 (first published 1990), p. 343.

- ↑ Wittgenstein, Ludwig. Culture and Value. University of Chicago Press, 1984 (first published 1946), pp. 48-49.

- ↑ Cohen, M. Philosophical Tales. Blackwell, 2008, p. 216.

- ↑ Monk, Ray. Ludwig Wittgenstein: The Duty of Genius. Penguin, 2001 (first published 1990), pp. 23–25.

- ↑ Wittgenstein, Ludwig. Culture and Value. Oxford 1998, p.16e; also see pp.15e-19e.

- ↑ Drury, M.O’C. “Conversations with Wittgenstein,” in R. Rhees (ed.). Recollections of Wittgenstein. Oxford University Press, revised edition, 1984, p. 161.

- ↑ Sluga, Hans D. The Cambridge Companion to Wittgenstein. Cambridge University Press, 1996, p. 2.

- ↑ See Wittgenstein, Ludwig. Remarks on Colour. Wiley-Blackwell, 1991.

- ↑ The Cambridge Wittgenstein Archive

- ↑ John, Peter C. "Wittgenstein's "Wonderful Life", Journal of the History of Ideas, volume 9, issue 3, July–September 1988, p. 510.

- ↑ Edmonds, David and Eidinow, John. Wittgenstein's Poker. Faber and Faber, 2001, p. 35ff.

- ↑ White, Roger. Wittgenstein's Tractatus logico-philosophicus. Continuum International Publishing Group, 2006, p. 145.

- For a discussion about the relative merits of the translations, see Morris, Michael Rowland. "Introduction," Routledge philosophy guidebook to Wittgenstein and the Tractatus. Taylor & Francis, 2008; and Nelson, John O. "Is the Pears-McGuinness translation of the Tractatus really superior to Ogden's and Ramsey's?, Philosophical Investigations, 22:2, April 1999.

- See the three versions (Wittgenstein's German, published 1921; Ramsey-Ogden's translation, published 1922; and the Pears-McGuinness translation, published 1961) side by side here, University of Massachusetts, accessed 4 September 2010.

- ↑ Russell Nieli. Wittgenstein: from mysticism to ordinary language. SUNY Press, 1987, p. 1999.

- ↑ 80.0 80.1 80.2 Hacker, P.M.S.. "Wittgenstein, Ludwig Josef Johann," in Ted Honderich (ed.). The Oxford Companion to Philosophy. Oxford University Press, 1995, pp. 912–916.

- ↑ Tractatus (OT), preface.

- ↑ Tractatus (OT), 6.54.

- ↑ "Wittgenstein's Manuscripts", Cambridge Wittgenstein Archive. Retrieved 6 September 2010.

- ↑ "Synopsis omitted by the author's special request - Ed." (p. 202), Scott, J. W.: 1949, 'A Synoptic Index to the "Proceedings of the Aristotelian Society": 1900-1949', Proceedings of the Aristotelian Society 50, iii-127.

- ↑ PI, §23.

- ↑ Philosophical Investigations, §107.

- ↑ Lear, Jonathan. "Leaving the World Alone". In Williams, Meredith (ed.). Wittgenstein's Philosophical Investigations: Critical Essays. Rowman and Littlefield, 2007, pp. 210.

- ↑ Cf. Philosophical Investigations, §309.

- ↑ Shanker, S., & Shanker, V. A. Ludwig Wittgenstein: Critical Assessments. Croom Helm, 1986, pp. 50–51.

- ↑ Gellner, Ernest. Words and Things. Routledge & Kegan Paul, 1979, originally published 1959.

- ↑ Perloff, Margorie. Wittgenstein's Ladder: Poetic Language and the Strangeness of the Ordinary. University of Chicago Press, 1996.

- ↑ Midgette, Anne. "At 3 Score and 10, The Music Deepens", The New York Times, 28 January 2005.

- ↑ Tait, Simon. "Wittgenstein's Symphonic Premiere", The Independent, 27 November 2003.

Further reading

- Baker, G.P. and Hacker, P.M.S. Wittgenstein: Understanding and Meaning. Blackwell, 1980.

- Baker, G.P. and Hacker, P.M.S. Wittgenstein: Rules, Grammar, and Necessity. Blackwell, 1985.

- Baker, G.P. and Hacker, P.M.S. Wittgenstein: Meaning and Mind. Blackwell, 1990.

- Brockhaus, Richard R. Pulling Up the Ladder: The Metaphysical Roots of Wittgenstein's Tractatus Logico-Philosophicus. Open Court, 1990.

- Fonteneau, Françoise. L’éthique du silence. Wittgenstein et Lacan. Seuil, 1999.

- Glock, Hans-Johann. A Wittgenstein Dictionary. Blackwell, 1996.

- Grayling, A.C. Wittgenstein: A Very Short Introduction. Oxford University Press, 2001.

- Guetti, James. Wittgenstein and the Grammar of Literary Experience. University of Georgia Press, 1993.

- Hacker, P.M.S.. Insight and Illusion: Themes in the Philosophy of Wittgenstein. Clarendon Press, 1986.

- Hacker, P.M.S. "Wittgenstein, Ludwig Josef Johann," in Ted Honderich (ed.). The Oxford Companion to Philosophy. Oxford University Press, 1995.

- Hacker, P.M.S. Wittgenstein's Place in Twentieth Century Analytic Philosophy. Blackwell, 1996.

- Hacker, P.M.S. Wittgenstein: Mind and Will. Blackwell, 1996.

- Harré, Rom and Tissaw, Michael A. Wittgenstein and Psychology: A Practical Guide. Ashgate, 2005.

- Kitching, Gavin. Wittgenstein and Society: Essays in Conceptual Puzzlement. Ashgate, 2003.

- McGuinness, Brian. Wittgenstein in Cambridge: Letters and Documents 1911-1951. Wiley-Blackwell, 2008.

- Monk, Ray. How To Read Wittgenstein. Norton, 2005.

- Nieli, Russell. Wittgenstein: from mysticism to ordinary language. SUNY Press, 1987.

- Pears, David. The False Prison, A Study of the Development of Wittgenstein's Philosophy, Volumes 1 and 2. Oxford University Press, 1987 and 1988.

- Sterrett, Susan G. Wittgenstein Flies a Kite: A Story of Models of Wings and Models of the World. Pi Press, 2005.

- Works referencing Wittgenstein

- Doxiadis, Apostolos and Papadimitriou, Christos. Logicomix, a graphic novel about Bertrand Russell and his relationships.

- Doctorow, E.L. City of God. Plume, 2001, depicts an imaginary rivalry between Wittgenstein and Einstein.

- Duffy, Bruce. The World as I Found It. Ticknor & Fields, 1987, a recreation of Wittgenstein's life.

- Jarman, Derek. Wittgenstein, 1993, a biopic of Wittgenstein with a script by Terry Eagleton (published by the British Film Institute, 1993).

- Jormakka, Kari. "The Fifth Wittgenstein", Datutop 24, 2004, a discussion of the connection between Wittgenstein's architecture and his philosophy.

- Kerr, Philip. A Philosophical Investigation, Chatto & Windus, 1992, a dystopian thriller set in 2012.

- Markson, David. Wittgenstein's Mistress. Dalkey Archive Press, 1988, an experimental novel, a first-person account of what it would be like to live in the world of the Tractatus.

- Scheman, Naomi and O'Connor, Peg (eds.). Feminist Interpretations of Ludwig Wittgenstein. Penn State Press, 2002.

- Wijdeveld, Paul. Ludwig Wittgenstein, Architect. MIT Press, 1994.

- Wallace, David Foster. The Broom of the System. Penguin Books, 1987, a novel.

- External links